Experts say Darwin’s work has been tarnished by feuding extremists from both science and religion

“In the beginning,” the Book of Genesis starts, “God created the heavens and the earth.”

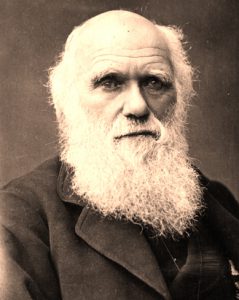

And that’s the way it was for thousands of years, until Charles Darwin came along and threw a monkey wrench into the grand design of life with On the Origin of Species.

But it’s not entirely Darwin’s fault his evolutionary theory created a divide between some in the religious and scientific communities, says Daniel Osmond, professor emeritus of physiology at the University of Toronto.

“People think of him as the bad guy because his name is so closely identified in a special way,” he said March 6. “So, Darwin becomes the dirty word; he’s the demon of the piece.

“But in fact I think he was drawn by his own observations rather inexorably, and was a somewhat reluctant, even confused convert to what is now called — in rather strident terms — Darwinism.”

The disinclination to accept his own theory stems from Darwin’s motivation to become a clergyman and the fear of offending his devout wife, Emma, Osmond said.

“I think he had enough consciousness himself and enough sensitivity to those around him that he didn’t really set out to embarrass in any way,” Osmond said. “I don’t think he was out to destroy spirituality.”

The humanist in Darwin is one of many focuses for the Royal Ontario Museum’s new exhibition, Darwin: The Evolution Revolution, which opened March 8.

Put together by the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, the exhibition ties together all facets of the Englishman’s life with some of Darwin’s own personal effects, a geological hammer, a microscope, a ticket to his Westminster Abbey funeral, 18 original pages from his On the Origin of Species manuscript and specimens collected while aboard the HMS Beagle.

And when it comes to the ideological spats Darwin has evoked, the ROM’s senior curator of natural history, Chris Darling, puts them to rest.

“Basically we present it from the perspective of science, not of cosmology, not of metaphysics or anything else,” he said. “When you take a purely scientific approach to this study of nature — there’s only one and that’s the scientific one.”

David Tessaro, head of the science department at St. Michael’s College, echoes Darling’s perspective, adding there is minimal conflict between evolution and Christian doctrines.

“(Our) position as religious educators and Catholic educators is that we’re not in the business of arguing against facts,” he said. “The facts of evolution speak for themselves, and they do not negate any sort of Catholic beliefs whatsoever.”

However, it is the extremists — adherents of Scientism and Creationism — that help perpetuate the myth of contention, Osmond said.

“We have this deep, historic story that poses the two protagonists, Darwin and the Bible, and they’re enemies, and you’ve got to keep arguing,” he said. “I don’t think Darwin saw it that way and I don’t think most serious Christians today necessarily see them as enemies.”

Debate aside, Osmond is enthusiastic about the ROM’s presentation of Darwin, adding his own position accommodates both sides.

“The traditional Christian faith includes the notion that God uses various natural agencies to exercise His will,” he said. “So, to me there is no contradiction between God’s ultimate creatorship.”