Comic books are known for their fantastical characters, dynamic artwork and controversy, but are they useful mediums to get fickle teenagers and kids to turn the page?

George Zotti, manager of the Silver Snail, a Toronto comic book retailer, seems to think so, but adds it can be difficult to pick up a title and immediately follow the story.

“The only problem with buying the standard comic book is that the stories continue from one issue to the next — they’re serialized,” he says, adding some story arcs span months, which can make it difficult for new readers to follow.

His solution is to get parents to buy trade paperbacks — including anime and from the ever-adapting publishers Marvel and DC — which include entire story arcs in one book.

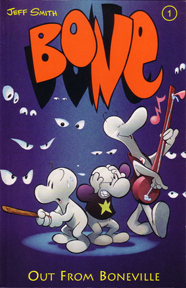

One title in particular, Bone, by artist Jeff Smith is great for introducing kids to the form, Zotti says, as the books grow with the child reading it.

“It’s got a lot of fun, kinetic energy to it, but is a fantasy book, even though the three main characters … are little white blobby guys called bones.”

And the anime trend is credited with keeping the industry from becoming predominantly adult focused. The Japanese version of comic books has jumped the Pacific with popular titles like Naruto and Bleach.

“Anime certainly has its audience now,” Zotti says. “It’s certainly pulling in a younger reader.”

For industry officials, the injection of anime is a refreshing change from the overpowering, moribund superhero genre.

“I’m a very big anime fan; I’ve been a fan even before it came to North America,” says Marvin Law, the Art Director at Toronto’s own comic publisher Bright Anvil Studios. “It’s good to bring in outside voices to the world, instead of us just staring at our own animation.”

For Law, the North American market has many flaws; including patronizing the reader, a problem he says has led to many youth closing the covers on comic books.

“The problem with a lot of the comic books targeted towards children is they talk down to them,” he says. “It’s pretty much treating kids like they are not smart enough to understand what’s going on.”

The patronizing stems from wanting to censor kids to adult content, Law says, adding children will just see R-rated subject matter elsewhere.

“Since the advent of the internet, I’m sure kids have seen things 10 times worse than in comic books,” he says. “We can shelter them all we want, but they’re going to see it anyway.”

Comic book standards have loosened up since the Comics Code Authority, an American content regulator created in 1954, has lost its power in the industry.

What followed was a variety of genres that have flooded the market, offering readers of graphic novels more options and the untying of artists and writers’ hands.

“The Comics Code Authority made the industry extremely careful and self-aware concerning what they published,” says Park Cooper, Editor-in-Chief of North York-based Septagon Studios Inc.

After the authority’s power ebbed, the comic book industry flourished.

“It’s created a wider range of comics, so that truly anyone can find something to their tastes,” he says. “Exploring little besides all-ages superheroes for so long led … to an explosion of different genres, styles and approaches in American comics that is continuing even now.”

With the new approaches, even Hollywood is getting involved, adapting some of the more popular characters like Spiderman, Batman and Iron Man to the silver screen.

Comic books may even wind up online, much to the chagrin of Law.

“As much as I hate to admit, I think comic books will really go online,” he says. “This generation has the Internet, and they’re used to reading online, as opposed to my generation that is used to reading the physical copy in their hands.”

But Law doesn’t see the hard copy going away anytime soon, and Cooper agrees.

“The answer is ‘yes’ only if one foresees a future when all new media is digital. If you don’t see that happening soon, then I’d say the answer is no,” he says.