The moment the U.S. military decided to reclassify Muhammad Ali’s service from 1-Y to 1-A, the world (Toronto included) would never be the same. Intrepid reporters would descend on the small Miami home of the man then known as Cassius Clay, not far from his training grounds. The 24-year-old had failed his previous two exams, and was exasperated they decided to conscript him now.

The moment the U.S. military decided to reclassify Muhammad Ali’s service from 1-Y to 1-A, the world (Toronto included) would never be the same. Intrepid reporters would descend on the small Miami home of the man then known as Cassius Clay, not far from his training grounds. The 24-year-old had failed his previous two exams, and was exasperated they decided to conscript him now.

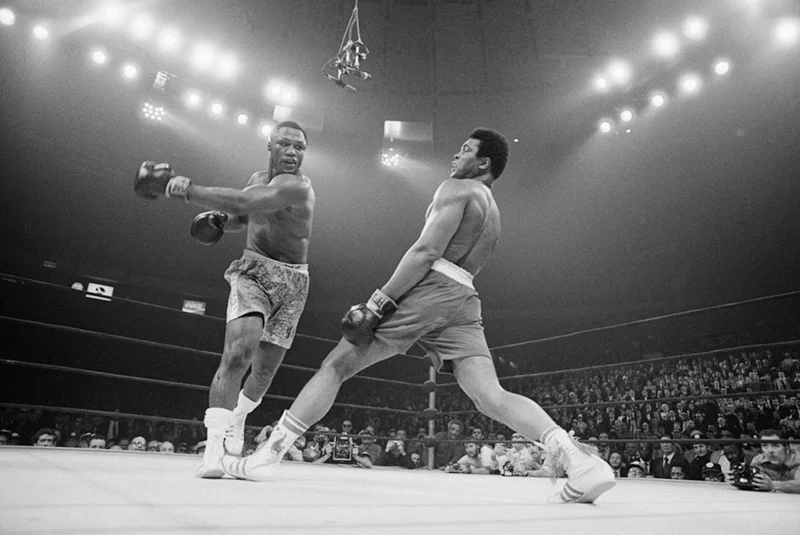

Ali was in fight mode. Preparing for a March 29 tilt against Ernie Terrell in Chicago, his days were spent training at Angelo Dundee’s Fifth Street Gym. Nights provided a chance to unwind. But on one particular day in March, 1966 unwinding turned into a sign of acquiescence.

It’s over 100 degrees Fahrenheit in Las Vegas. That’s 40 degrees Celsius if you’re talking metric, but either way you punch it in, it’s enough to fry an already addled boxer’s mind. A tired voice manifests itself from the phone. It belongs to Bob Arum, the promoter who was pushed into his start in ’66 by football player Jim Brown. It’s the day of Manny Pacquiao’s announcement he’ll return to the ring, and Arum’s planning for that as well as the Terance Crawford-Viktor Postol bout set for July 23. And Arum shared what really went down in Miami and Chicago on the day Ali said he has no “quarrel with the Viet Cong”.

He offered an obligatory “let me give it to you” during the phone call and unraveled the bind that the Greatest of All Time (GOAT) found himself in after he refused to serve in the army when they would come calling. And they did in April, 1967.

“They reclassified him in response to the public protest that here was this big, strong guy, how come he wasn’t eligible to serve,” Arum recalled, replaying the surreptitiousness of the media when the story broke on CBS. By dinner time, the United States would know of the heavyweight title holder’s dissension. When Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley heard the buzz, out went the lights.

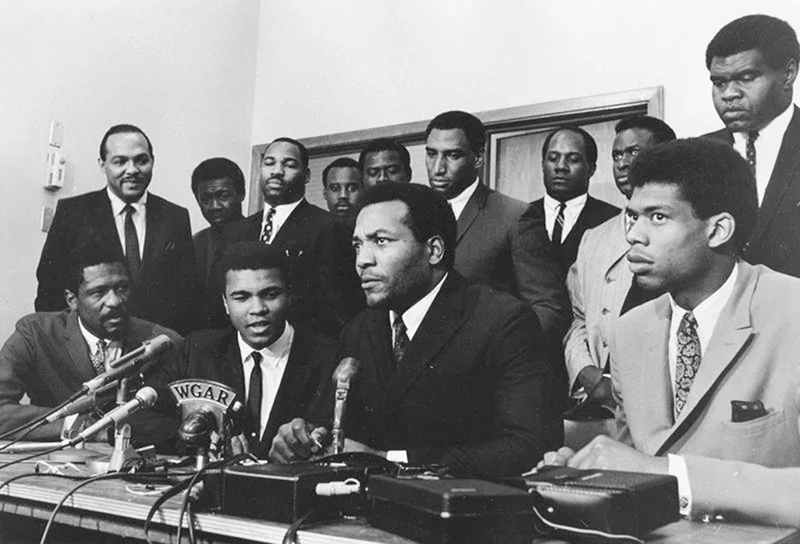

“We were busy selling tickets for the fight in Chicago, and the original Mayor Daley, who is a bit of an authoritarian, turned back on the deal and told the Boxing Commission to not allow the fight to go on,” Arum said. Of course, that sent everyone scrambling for solutions. Arum quickly appealed to the Illinois State Athletic Commission, requesting at least a hearing for Ali. They agreed, and Ali was brought up; but not without making a stop at the residence of his mentor, and leader in faith, Elijah Muhammad.

“(Elijah) convinced him that the position he was taking was correct, and Ali told the Illinois Commission that he would not go into the service,” Arum said. “As a result of that, they threw us out of Chicago, and it became apparent to me, based on statements made by cities across the States that no one would welcome the fight to be held in that city.” He’s right. Most Americans were aghast that Ali had the audacity to thumb his nose at the military and dodge the draft. Ali still had his passport, however, and a chance to fight Ernie Terrell somewhere else on the continent.

The first stop was the Forum in Montreal. It seemed like a good fit, but the American Legion was already pressing hard. They threatened Mayor Jean Drapeau that they would boycott the World’s Fair, Expo ’67, if he allowed the fight to happen.

A stunned Arum didn’t know what to do. But the fates would be with him, as Harold Ballard, co-owner of Toronto Maple Leafs and Maple Leaf Gardens, called him.

Welcome to Hogtown, GOAT!

Back when the evidence of Toronto’s nickname was still inhabiting the stockyards of Runnymede Road and St. Clair Avenue West, Hogtown would become host to a big-ticket fight. Arum remarked that, when he returned to Toronto in March of this year, he barely recognized the city from his visits during the ’60s. Still, Toronto was the home of Harold Ballard, and the irascible co-owner — who the previous year forced the Beatles to play two shows on the same day — was interested in bringing Ali to the city.

“When I got there, he said he was having problems with his partner, Conn Smythe, who didn’t want Ali in the building,” Arum recalled. “Smythe said, ‘I don’t want that draft dodger here’.” Of course Smythe would say that: he was a decorated veteran of both world wars. Still, most of the co-ownership of the Leafs was with Conn’s son Stafford, as well as newspaper owner John Bassett and Ballard. Conn eventually resigned from his position, and quit the board of governors over the fight. “As a result, I thought that was it,” Arum said. “(But) Harold felt strongly about it.”

It goes without saying that, in Toronto, Ballard was not a beloved hero. He was often perceived as miserly and authoritarian. The owner of the Maple Leafs had public rows with his players, chiefly team captains Dave Keon and Darryl Sittler. Ballard would be convicted on 47 of 49 counts of fraud in the early ’70s. He went to jail, and was paroled in October, 1973. But that’s his history, and for the time being Ballard was looking to host a fight for Muhammad Ali when no other city in North America was offering.

“Harold Ballard was a tremendous presence: he spoke with great authority, and he was very loud in articulating his beliefs, and he was very determined,” Arum recalled. “You could see that if he felt he was in a fight he would be the kind of guy that would engage in it, rather than temper the situation and avoid the fight.”

It looked like the fight was still on until Terrell flaked. He had heard the American Legion was going to put up picket lines around closed-circuit television venues in the United States. A big source of revenue would be cut off. So, with 20 days to go Canadian heavyweight George Chuvalo would come forward to take his first attempt at the world title. But the drama wasn’t over.

The Ministry of Labour had no objections, but the Ontario Boxing Commission took its time sanctioning the fight, because they didn’t believe Chuvalo was good enough.

“We ended up doing the fight — saving the bacon, so to speak — and civil rights leaders told Jim Brown that if we hadn’t have pulled this off it would have been a tremendous blow to the civil rights movement,” Arum said. “Because it meant the white establishment could inflict punishment on a black person who had the temerity to speak out and articulate his beliefs.”

Civil rights had reached a fever pitch in the United States. The three Selma-to-Montgomery (Alabama) marches, beginning with the infamous Bloody Sunday, took place the year then-President Lyndon B. Johnson was fine-tuning the Voting Rights Act, which would be enacted in August, 1965. Martin Luther King, Jr. had also set the wheels in motion for the Chicago Freedom Movement, events that would reach their heights in July, ’66. It’s odd hearing the name Ballard and Civil Rights Movement in the same sentence, but Arum attests to the connection.

“Toronto and the unsung hero, Harold Ballard, made (the Ali fight) happen,” he said. “He should have a significant part in civil rights history in the United States, and as a symbol of openness and tolerance, which the Canadian people are known for.”

The Toughest Ali’s Ever Fought

When it comes to singing praises, Chuvalo has plenty for his adversary in the ring. That March 29, 1966 fight was his first shot at the world title, and he was intent on claiming it. But when it comes to behind the scenes, it didn’t really matter what happened.

The phone crackled with the life of Chuvalo’s voice, in the present day. It’s brusque but gentle, the same way a grandfather shares war stories with his grandchildren. He started to share his role in the historic fight.

“Do I fight him in Toronto, or I’ll fight him somewhere else? I didn’t care. What I wanted to do was take the fight,” he said. “It was up to the promoters to find out who is involved, and they decided to take the opportunity to fight here in Toronto.

“It was a great thing for me to fight Ali in front of my hometown crowd.”

Of course it was, and he hung in for all 15 rounds of punishment. There was always a hope for him to win, to stage an upset over the GOAT, even if Ali had won most of the rounds. But that would require a KO. It wasn’t until the final round, where he let loose with a few shots — good enough to elicit a “Chuvalo may have hurt Clay!” from fight caller Don Dunphy. Chuvalo had only 17 days to prepare for the fight, and though he was in decent shape, he wasn’t in peak condition. There’s a moment of rueful recollection.

“It was a rush job,” he admits now. “It was like I had a date with a beautiful woman and I was in a hurry.

“You’ve got to get dressed up, take a shower, use a nice cologne. You have to prepare yourself, right?” It was enough time to make the fight interesting, though. Chuvalo’s strategy was to get Ali on the ropes so he could immobilize him by putting his head against his chest. But Ali was too fast.

“I had the shot to knock him out, but I just couldn’t finish him,” Chuvalo recalled. “I know in the fifth round I rocked him pretty good, but he recovered and he was a tough guy.”

The two would become great friends, and would also meet again in the ring, this time in Vancouver, B.C., on May 1, 1972. Which is why it would later be tough on the Toronto-born boxer to see his colleague suffer at the hands of another adversary, Parkinson’s Disease. Ali lauded Chuvalo throughout his career, calling him the toughest guy he ever fought. For Chuvalo though, the fight was a benchmark of his career, and a life that had battles that shouldn’t have to be fought.

“That’s what people remember you by,” he said. “With me, if there is any one question about my career, and I meet somebody and we get talking, it’s what was it like to fight Muhammad Ali? And I tell them it wasn’t a lot of fun.” He laughed. His voice swelled, like an eye after a few rounds. He admitted he was unable to attend Ali’s funeral service in Louisville, Ky. following his June 3 death but paid his own respects by reminiscing.

“It will always be something that I hold near and dear to myself,” he said, of the fight they had in ‘66. “If I think about the event, think about the excitement, and think about the chance I had.

“It’s a thrill to think about it in my own mind, privately, and it is something that will last forever.”

What if… ?

There is no prophet hidden inside Arum. He’s reluctant to speculate on the what-ifs or alternate histories in which Toronto was not opening its doors to Ali. But he does posit the civil rights movement would have been impeded.

“I know it would have been a really serious blow to the civil rights movement,” he said. It was, however, a gateway to his next four fights, as he still had his passport. That document would be taken away from him a year later. He would go on to face Henry Cooper and Brian London in London, U.K., and then Karl Mildenberger in Frankfurt, West Germany, all within the year. He would also wrap up the year with a match against Cleveland Williams in Houston, Tex. There were no concerns returning Stateside to fight at the Astrodome. The stadium owner, (Judge) Roy Hofheinz, kept them protected. As for the direct results from the Toronto fight, Ali received payment from the proceeds, the American Legion did not picket closed-circuit television locations, or bars, and it enjoyed a modicum of success.

“The fight didn’t do gangbuster business, but it did do enough to show profit,” Arum recalled. “It gave Ali the springboard where promoters in London and Germany were able to do three Ali fights in short order that summer.”

Keeping the history alive

An Ali fight is a great moment for Toronto sports history, especially if you ask Global Legacy Boxing president Les Woods. Back on March 29 — 50 years to the day — Woods, along with British-Canadian boxing legend Lennox Lewis, honored Chuvalo, Arum and Ali, via daughter Rasheda, with a gala dinner at the Mattamy Athletics Centre — the former home of Maple Leaf Gardens. Toronto Mayor John Tory attended the event.

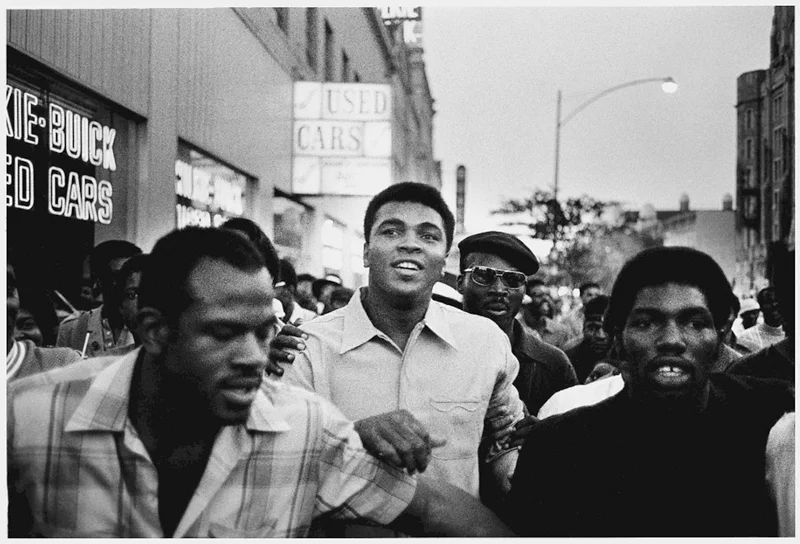

Toronto was the last city to publicly honor Ali before his passing on June 3, 2016. Like many boxers, Lewis was immensely inspired by Ali.

“This was something we refused to let pass without being publicly recognized — because it’s a part of history, and boxing has a big history in Toronto,” he said, speaking from New York City. “Just because we don’t show boxing on TV like we should, we don’t want to let the next generation go by without understanding what really took place.”

“It was a big moment back then.” Woods echoes the sentiment, and is not shy to say that Toronto extended the opportunity to defend his title and continue fighting.

“Toronto was pivotal for Ali,” Woods said. “The movement he created grew significantly as a result of Toronto welcoming him, and supporting him to continue boxing.” There’s a sense of awe that can be detected in Woods’s voice when he shares the stories Arum told him during his stay for the 50th anniversary gala dinner.

“(Arum) was single-handedly responsible for bringing Muhammad Ali to Toronto. It was his promotion. Ironically, that was the first fight he had ever promoted.” Woods called Arum’s work with Harold Ballard “brilliant.”

“How impactful that was on Muhammad Ali’s life, and the change it created,” he said. “Toronto helped forge a legacy that has been carved out in sport’s history for all time.”

It’s only fitting then that British-Canadian boxer Lewis would be named a pallbearer at the funeral. Woods also attended what became a remarkable celebration, where a variety of notable people from all walks of life paid tribute to the boxing legend.

“Despite the unfortunate circumstances in which everyone was gathered, more importantly, it was the celebration of an icon’s life. He made a difference, touching numerous lives, and was an inspiration to so many people,” Woods said. “They were so appreciative of the opportunity Toronto and Canada provided for Muhammad Ali in 1966, at a time when America turned its back.” Lewis said being a pallbearer was both “an honor and a privilege.”

“Despite the unfortunate circumstances in which everyone was gathered, more importantly, it was the celebration of an icon’s life. He made a difference, touching numerous lives, and was an inspiration to so many people,” Woods said. “They were so appreciative of the opportunity Toronto and Canada provided for Muhammad Ali in 1966, at a time when America turned its back.” Lewis said being a pallbearer was both “an honor and a privilege.”

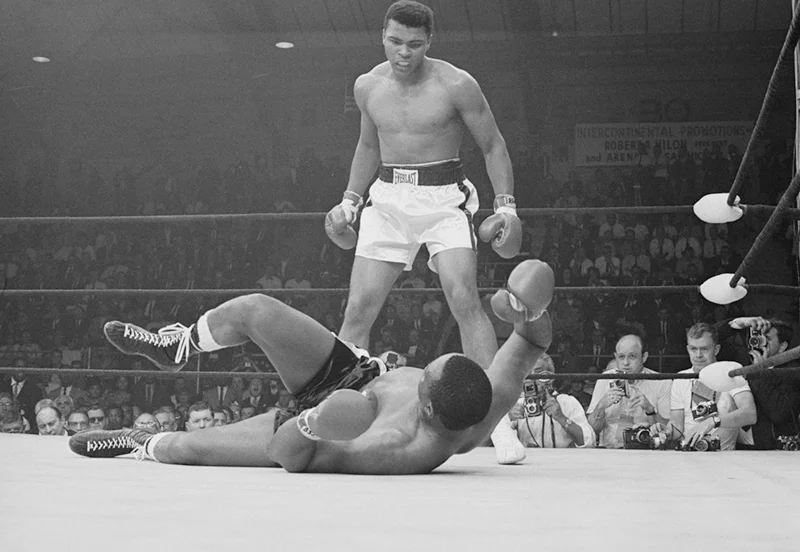

Ali was an inspiration for him, and the first rule for a young boxer was to float like a butterfly and sting like a bee, as stated by the GOAT before his match in ‘64 against Sonny Liston.

“That’s the anthem to the boxing profession,” Lewis said.

It was Ali’s wishes to have Lewis as a pallbearer, as it connected him with one of his favorite boxers from an era after his own. “The last thing he told me when he came to Toronto — and I remember this distinctly — ‘I used to be the champion, and now you’re the champion’,” Lewis recalled. “And I said, ‘You’ll always be the greatest’.”

More than a movement

It’s not just the civil rights movement that benefitted from the 24-year-old Ali’s resistance to war.

After his retirement from boxing, Ali was named a United Nations Messenger, raised money for Parkinson’s Disease research, supported the Special Olympics and Make-a-Wish Foundation, and travelled abroad to places like Afghanistan and Morocco.

He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom from George W. Bush in November, 2005, and the President’s Award from the NAACP in 2009.

Perhaps Chuvalo said it best, when he first described Ali, calling him “the greatest heavyweight champion we’ve ever had.”

Finally, if there had been no George Chuvalo, who would have fought Ali in his first fight outside of America? It’s quite possible that no one would step forward.

“I’m glad the fight happened,” Chuvalo said. “I’m glad I was able to take part in something like that.

“I got my shot. I didn’t win the fight, but I had a good time.”

Given all the drama surrounding the big fight, it appears Ali had a good time too.