Cindy Crawford with Katherine O’Leary

Rizzoli New York

Hardcover/253 pages

3.5 out of 5

Supermodel opens up about work, relationships and motherhood

I’m not particular on celebrities, and I’ve interviewed enough people with a modicum of success to lose that star-struck sheen from my eyes.

But if there’s one celebrity that could possibly make me a little weak in the knees it’s Cindy Crawford.

As a teenager, I had a couple of her posters on my wall, in particular a Marco Glaviano shot from her 1991 calendar. I was even hoodwinked into drinking Pepsi because of her (the rare moment of weakness to marketing).

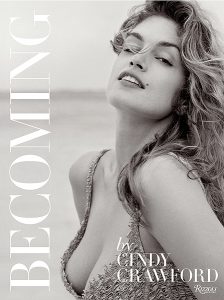

So, when I heard of her autobiography, Becoming — written with Katherine O’Leary — my interest was piqued.

Its format is typical of the fashion publication: 8.5″ x 11″, lots of photos and a textured cover. And at $50 (the same both in the U.S. and Canada, thankfully), it’s a tough sell those who are not interested in fashion or the supermodel.

With all the photos, there isn’t as much to read — carve the 253 pages (acknowledgements included) up into a third, and you can breeze through this volume in a couple of hours.

And that’s what needled me. There wasn’t enough.

As a teen, Crawford was probably the only celebrity I paid enough attention to know she had been rewarded an engineering scholarship to Northwestern, she unfortunately lost her young brother, Jeff, to leukemia, and that she grew up in De Kalb, Ill.

But when she started sharing her tales of working with the likes of Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, Arthur Elgort, Patrick Demarchelier, Helmut Newton and Herb Ritts, I wanted to hear more.

Instead, we are treated to some famous shots, and one or two anecdotes about her professional relationships with the photographers, including the man who started shooting her in Chicago, Victor Skrebneski.

That’s not bad, but it does make you feel a little hollow since this was Crawford’s bread and butter for years, if not decades.

As a person who has a deep interest in the works of these shutterbugs, though, including other famous photographers, I wanted to see the body of work, rather than just a print and a cutline.

In a way it does work though, as it’s a Polaroid shot of the working relationship. A test if you may, that many models stand in front of a blanched wall to take as they reach for supermodel-dom.

It’s funny when you remember certain benchmarks of pop culture, you realize the supermodels of the ’90s were there. Crawford shares her popularity from George Michael’s “Freedom ’90” video to the Pepsi ads to MTV’s House of Style.

There’s very little on her marriage to Richard Gere, only the lessons learned, and shared in a somewhat rose-tinted manner, if only vaguely.

And she’s candid about those brushes with notoriety, in particular her Vanity Fair shoot with k.d. Lang that clearly irked many mid-class Americans.

The depth of Crawford’s writing does hit the two-metre mark, and that comes with the more close-to-home tales.

“Modeling is just my job, it’s not who I am,” is one of her more well-known lines, and it’s shared. And I appreciate her candour about becoming a mom, maintaining a 30-year-career in the industry.

There is more passion in this part of the book. It’s done so in that bare-bone language that is prevalent throughout, but here, in the more vulnerable aspects of her life, it works.

Interesting, Crawford opens up about the decision to write a book about her life. Perhaps that trepidation comes through in her writing, and wasn’t completely whitewashed

Or it’s simply a harkening back to her Midwestern roots. The country girl who excelled in school and juggled modelling with engineering classes in Chi-Town.

I think one quote from her book sums it up nicely.

“Not that I believe you can have it all: I believe you can have it all, just not at the same time.”