PRAYER BOOKS AND HOPE: Yuri Dojc shoots photos of Jewish prayer books from around the world for his project Last Folio. Eight of his works have been selected as part of the Memory Unearthed: The Lodz Ghetto Photographs of Henryk Ross exhibition at the AGO.

Yuri Dojc’s Last Folio captures the emotion behind Jewish prayer books

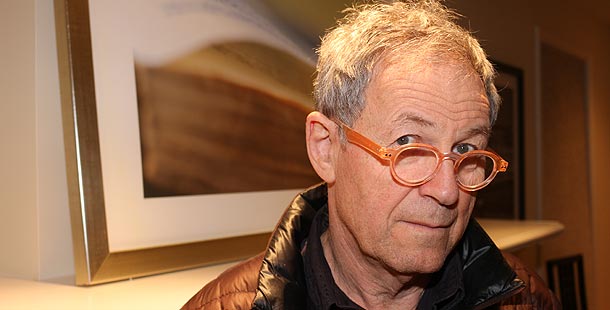

Life is not perfect, at least through the lens of Yuri Dojc, a well-seasoned photographer in midtown.

He’s weary from globe trotting, having spent the last month in Nicaragua, the U.S., England and Latvia, and he’s candid about his work Last Folio being presented as part of the Memory Unearthed: The Lodz Ghetto Photographs of Henryk Ross exhibition, showing until June 14 at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Dojc’s photos are meant to leave visitors with a sense of absolution, after witnessing the stark black and white images of Ross, a Polish Jewish photographer who captured the grim images of his people in the Nazi controlled-ghettos of Lodz, Poland before they were sent to the death camps at Chelmno and Auschwitz.

Memory Unearthed curator Maia-Mari Sutnik approached Dojc in December to pick eight prints, sans frame, to hang in one of the four rooms sectioned off at the AGO. Its Jan. 31 launch came on the heels of Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Last Folio, an ongoing project started in 2005, is vivid depiction of old Jewish prayer books, mostly in his home country of Slovakia. Most of the photos are closeups, and the books are beautifully shown in various forms.

Most of all, they’re imperfect, obscured by the use of the aesthetic quality of bokeh.

“All those perfections become too perfect, and life is not perfect,” Dojc remarks, seated in the front room of his Lytton Park home. “And these books are not perfect.”

He confesses that he’s an artist first, and isn’t attempting to be a social activist. He does it mostly for the people he meets. One story, Dojc shares, was about a man in a wheelchair who approached him while in Daugavpils, Latvia.

Before the war in Yugoslavia, he was a karate champion. He was captured — Dojc admits not knowing which side — and the man’s legs were shot.

“It’s not really important what I think about what the message is,” Dojc says. “What is important, is what the message is for him.

“It’s for people to pause for a second, even to see how lucky you are.”

Dojc says that all too often during his travels he is overwhelmed by the raw emotions behind each book.

“Sometimes the emotions are so strong that after one book you’re so exhausted, especially if you open the book and there’s something written on the edge of the book,” he says, downcast. “I tell you, once we were in the roof of this building [in Latvia], we found some letters from kids. School essays. This one kid wrote that he wanted to be a forester, and you knew that he never had a chance, because he ended up in the camp.”

“After that, you just want to go away. You want to forget it, because it’s too heavy. What would lead people to do this?”

There’s talk of the current political landscape in Europe, the rise of the far right sneaking in through the European Union. Dojc is not a fan. His body language is hunched, defeated. But, he adds, the “left is just as bad, if not worse.”

“You just see what man is capable of doing to another man,” he mutters. “Your hope is that it never happens again, but that is just hope …

“You actually give up on that one, because it just happens anyway. You just hope that people who are crazy just don’t come to power.”